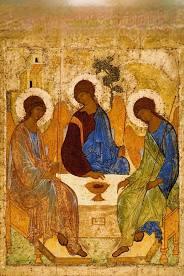

Just occasionally during the school trips to Russia that I led it was possible to allow the pupils some free time and to have an hour or two of pleasing myself in Moscow. On one of these occasions, I headed straight for the Tretyakov Art Gallery. The painting I most wanted to see was the one reproduced on the appendix to this week’s pew sheet. It’s a fifteenth century icon by the great Russian master Andrei Rublev. It’s usually spoken of as the Old Testament Trinity, though that’s not how Rublev would have named it. In his day, icons depicting this scene were known as the Hospitality of Abraham. On one level, the icon illustrates the story in Genesis of Abraham and his wife Sarah entertaining three angelic messengers, but on another level the three figures represent the three persons of the Holy Trinity.

The angel in the centre is dressed in a way that would have prompted Rublev’s contemporaries to recognise him as Jesus, and the fact that he is seated in the position of the host and the gesture of blessing he is making over the chalice in the centre of the table reinforce that identity.

Jesus gazes towards the figure who is seated on the left of the picture, the figure which represents God the Father. Jesus sees God with absolute clarity, understanding and love. The messages for us are precisely those which Jesus gives to Nicodemus in today’s Gospel when he says:

“…we speak of what we know and testify to what we have seen.”

and then we read that

“…God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, to that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”

Jesus looks towards God the Father, but he is painted in such a way that it seems that he has just turned his head in that direction and that a moment before he was gazing at the third figure, the one on the right of the image, the one that represents the Holy Spirit. That figure faces in the direction of Jesus and of God the Father. And in our Gospel reading Jesus speaks of the transforming power of the Holy Spirit, of the possibility of new birth in the Holy Spirit.

Together the three figures form a circle of mutual contemplation and love. The arched backs of God the Father and the Holy Spirit are two arcs of that circle.

Many people have found the doctrine of the Trinity difficult or even impossible and I have considerable sympathy with those difficulties. Yet without it there are other important things which become impossible to believe. The most important belief which makes no sense without the Trinity is the simple and vital proposition that you’ll find in the 1st Epistle of John:

“Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.”

Not “God is loving” or “God is compassionate” or “God is merciful”. Those are ways of speaking which we can apply to other human beings. “God is love” is a statement of a different kind. Love is about living in relationship, and for the words “God is love” to make sense, there has to be relationship within God, there has to be the mutual love and contemplation which the icon shows.

And what about us? We read in Genesis that we are made in the image and likeness of God. If God is loving and relational, we aren’t created to behave like self-made people, finding and asserting our individuality. We are made to relate lovingly one to another and to God. We are made to work together. As one of Susan’s carers said to me last week:

“Teamwork is Dreamwork.”

None of the figures in the icon is looking directly at us and yet the icon invites us in, encourages us to participate in the love of God the Holy Trinity. The three figures are seated on a platform and, if you look carefully, you will see that the perspective of that platform is reversed. It points towards us. There is an empty space at the table which we are invited to occupy. We too can be part of the circle of love.

Over the Christian centuries, writers and thinkers have used different word pictures to describe that invitation to belong to God the Holy Trinity. St Paul writes in today’s Epistle that we are invited to be “children and heirs” – members of a family. Some theologians have likened the Holy Trinity to a dance which we are invited to join. We might also think of it as the invitation to be part of a team. Andrei Rublev chose the metaphor of hospitality – Abraham’s hospitality to the angels seen as the Holy Trinity’s open and loving offer of hospitality to us.

To that invitation, the obvious, the honest reaction is “Who me? The person who is so often grumpy, bad-tempered and selfish?” That’s what the priest-poet George Herbert was getting at in the poem you will find beneath the icon.

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lacked anything.

"A guest," I answered, "worthy to be here":

Love said, "You shall be he."

"I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on thee."

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

"Who made the eyes but I?"

"Truth, Lord; but I have marred them; let my shame

Go where it doth deserve."

"And know you not," says Love, "who bore the blame?"

"My dear, then I will serve."

"You must sit down," says Love, "and taste my meat."

So I did sit and eat.

And so we are invited to be nourished and transformed by the God who is love.